A New Era Begins: First Images from the Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST)

by Adam Hadhazy

The Rubin Observatory’s landmark survey traces its origins to the founding of the Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology and a catalytic act of philanthropy.

The Author

Image credit: RubinObs/NOIRLab/SLAC/NSF/DOE/AURA

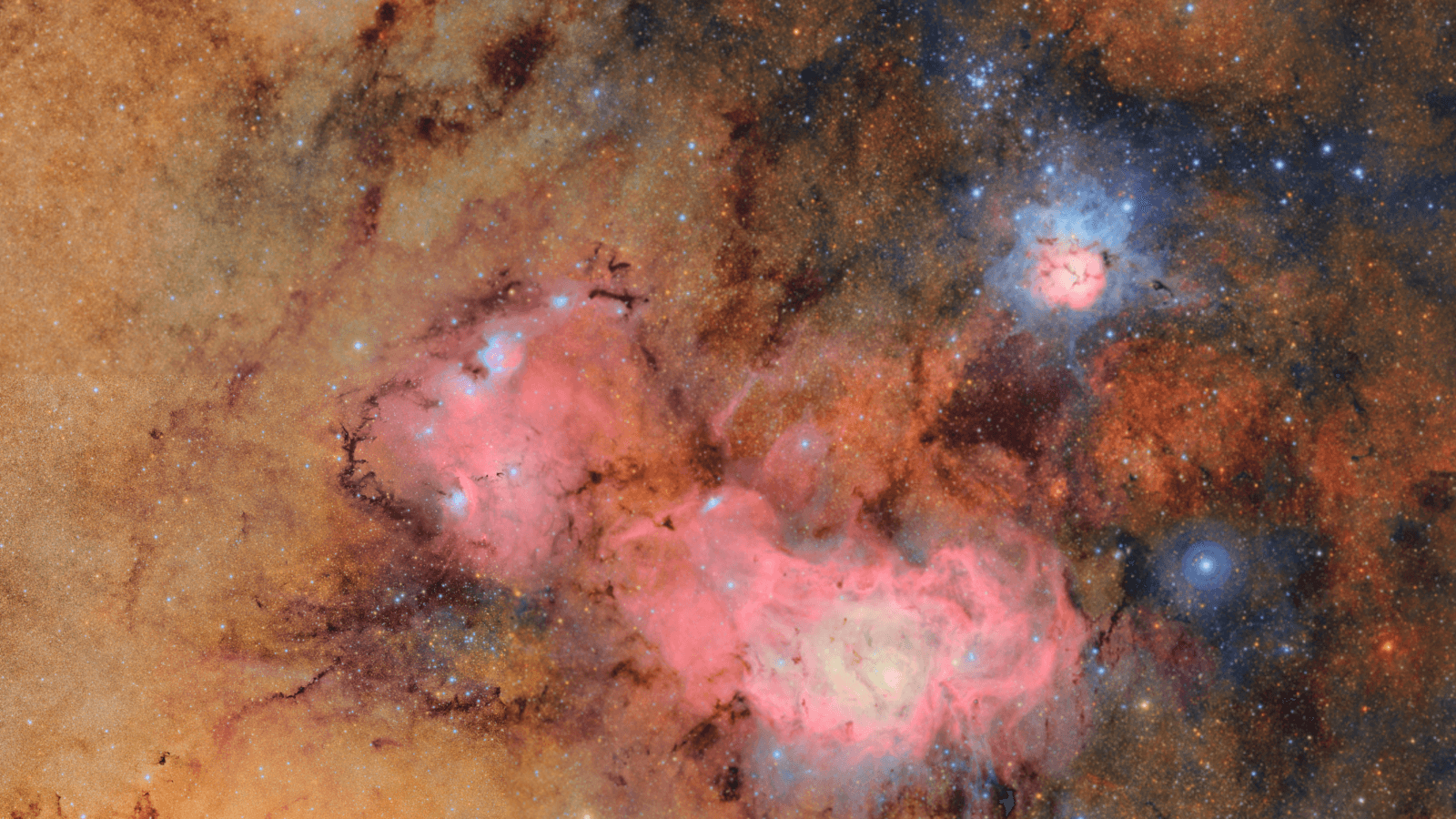

After three decades in the making, the Vera C. Rubin Observatory has reached a defining moment. In June, its first spectacular images—stunning glimpses of galaxies, nebulae, and asteroids—offered a hint of the revolutionary science campaign ahead: the Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST). Soon, LSST will begin scanning the Southern sky every few days, potentially delivering game-changing contributions to astronomy, physics, and cosmology.

With each nightly run, the 3.2-gigapixel, 6000-plus-pound digital camera—the largest ever made—will collect a whopping 20 terabytes of data. After just a year, LSST will have gathered more astronomical data than all previous telescopes combined. As massive as that haul will be, it represents a tiny fraction of LSST’s planned decade-long tilt at the skies. The survey’s full dataset will yield a 3D movie across billions of years of cosmic time.

For a project of this scale to succeed, it required institutions willing to collaborate in new ways. The founding of the Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology (KIPAC) in 2003 proved pivotal for the endeavor.

KIPAC was established as a joint institute of the physics department at Stanford University and the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Acceleratory Laboratory, with key funding from The Kavli Foundation. Through this institutional synergy, KIPAC and its members spearheaded the LSST project from its early stages all the way through to June’s milestone image release.

“The spark that lit the fire was the Kavli Institute,” recalls Persis Drell, a professor of materials science and engineering, a professor of physics, former Stanford provost, and former SLAC director. “LSST couldn't have happened—it wouldn't have happened—without having all the facets of a great research university, the federal government, and philanthropy.”

“It's a beautiful example,” she continues, “of how these facets have to come together to make something big and ambitious and new like this."

The rise of LSST

The first inklings of what would grow into the LSST emerged in the mid-1990s under the name “Dark Matter Telescope,” led by physicist J. Anthony “Tony” Tyson at the University of California, Davis. Various groups expressed interest in developing the idea, but it wasn’t until KIPAC’s formation that the project had a home base.

In 2001, then-SLAC director Jonathan Dorfan, together with the chair of the Stanford physics department at the time, Steve Chu, sought to bridge the long-estranged research communities of Stanford and SLAC by bringing them together into a newly proposed institute. In 2002, Caltech theoretical physicist Roger Blandford and Columbia University experimental physicist Steve Khan were being recruited as potential institute directors. However, the dot-com bubble burst, causing external funding to suddenly evaporate and leaving Drell, then an associate lab director, and others searching for a new sponsor.

Through Stanford connections, a meeting was arranged with Fred Kavli, who had made advancing human knowledge through science the mission of his recently established foundation. Drell showed Kavli around campus and discussed the immense potential for the fledgling institute. “I remember that I took him up on a balcony of another building and showed him what would be the view from the building we'd love to build with his name on it,” Drell recalls. “And I felt like that was the magical moment.”

Drell says that each party (Blandford, Kahn, and Kavli) was a “yes” in answer to the question of launching KIPAC—so long as everyone else was also on board. A chief reason why those three key individuals, along with many others, bought into the premise of KIPAC was LSST.

“When Roger and I individually visited for the director role, we talked about wanting to do a big project that is at the interface of particle physics and astrophysics. That was really exciting to me,” recalls Kahn, who would later serve as LSST director.

The match was natural. LSST’s particle detector-like complexity made SLAC, given its history in particle physics, the perfect place to develop and build LSST’s intricate camera.

“Roger and I, independently, had LSST on our minds,” says Kahn, now an emeritus professor of particle physics and astrophysics at Stanford, and since 2022, a professor of physics and astronomy at the University of California, Berkeley.

Blandford, for his part, remembers being highly intrigued by LSST’s potential for advancing the field of transient astronomy, the study of short-lived cosmic phenomena, such as exploding stars. These and other transients will be captured on a gargantuan scale by LSST’s field of view that spans seven full Moons, and a time domain that snaps the sky in fleeting, 15-second increments. “LSST will transform transient astronomy and be a discovery engine for so many researchers,” says Blandford, a professor of physics and of particle physics and astrophysics at Stanford.

Working together at KIPAC, with Blandford as director and Kahn as deputy director, they helped build the nascent science case for LSST. Kahn gave colloquia to high-energy physics groups nationwide, cultivating interest and gaining traction with funders at the Department of Energy (DOE) and the National Science Foundation (NSF).

Kahn fondly looks back on the major milestones for LSST, from the astronomical community blessing it with top-priority status in the 2010 Decadal Survey, to passing numerous critical decision points with supporting federal agencies, to seeing the camera designed, built, and tested at SLAC. He also recalls being on the ground in some of the remotest, driest places on Earth to help select the site for the Vera C. Rubin Observatory, ultimately built on Cerro Pachón in northern Chile, where LSST will be carried out.

Throughout the process, The Kavli Foundation remained steadfast, and the flexible funding played a catalytic role in moving the LSST forward. “There were a lot of hurdles,” says Kahn, “and there's no question Kavli was crucial to LSST.”

Carrying on the scientific legacy

Building on LSST’s success, The Kavli Foundation is continuing to support cutting-edge science at KIPAC with a recent $5-million commitment to a new initiative project called the Via Project. The effort is leveraging our own Milky Way Galaxy as a dark matter laboratory, seeking new insights into the mysterious substance estimated to comprise some 85% of mass in the universe.

Risa Wechsler, the Humanities and Sciences Professor and professor of physics and of particle physics and astrophysics at Stanford and SLAC, and KIPAC’s director since 2018, is a leader of the Via Project. She first came to Stanford in 2006 and helped develop the science case for LSST as a large-sky survey through cosmological simulations.

“LSST and the Rubin Observatory were definitely one of the reasons I wanted to get involved in KIPAC,” says Wechsler. “The first images are spectacular, and it’s so mind-blowing to think about what we're gonna be able to do with this survey.”

The Via Project will help the cause by using ground-based telescopes to measure the motion of stars and groups of stars in and around the Milky Way. Spectroscopically charting these stellar bunches will help researchers create the most detailed maps to date of dark matter’s gravitational imprint.

Directly tying in with LSST, the Via Project will use data gathered by the Rubin Observatory to supplement its own observations, starting in 2027. “With the Via Project, we hope to shed new light on the nature of dark matter and the formation of the Milky Way—carrying on the legacy of KIPAC in doing incredible things with The Kavli Foundation’s support,” says Wechsler.

The Kavli Foundation’s early backing was, in effect, a spark that helped make the LSST possible. Two decades later, its continued investment is ensuring that discoveries at KIPAC, and the legacy of LSST, will shape the future of astrophysics and cosmology for decades to come.

“We’re all grateful to the Kavli Foundation, and Fred Kavli in particular, for having the vision to invest in these astrophysics institutes,” adds Blandford. “I’m very honored to have been a part of it.”

Related Links:

Vera C. Rubin Observatory